ON FACEBOOK, A PICTURE IS WORTH A THOUSAND FRIENDS

by James H. Fowler and Nicholas A. Christakis

We are all embedded in vast, beautiful, complex webs of social relationships that influence a wide range of behaviors, attitudes, and emotions. In our book, Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape Our Lives, we chronicle a variety of phenomena that can spread in "real world" social networks. And we argue that connection and contagion are so fundamentally rooted in our evolutionary psychology that they carry over even to very modern aspects of human life – including email, blogs, and social networking sites.

To study whether social contagion can happen online, we started following a group of about 1,700 interconnected college students on Facebook about four years ago. Many people post information about their favorite bands, movies, and authors on their profiles, and we wondered whether these tastes tended to spread from person to person. At first we thought we would find evidence of social contagion between Facebook friends the same way we did between real-world friends in our past studies. But when we analyzed the network, we found that not one of the bands, movies, or authors people listed had any noticeable effect on whether any of their Facebook friends would also list the same bands, novels, or authors at a later date.

This makes sense, actually. What our past work has shown is that social contagion only works between people who have close social relationships. Even though we may have 1,000 "friends" online, the very tenuousness of these relationships means they may not be as powerful as a single real-world connection.

But how could we figure out which Facebook connections were also important, real-world connections? One idea we had was to use the tagged photos that people share with one another online. If you upload a picture of someone, the chances are good that you have a real-world connection with them. At the very least, if you physically took the picture, then you and the tagged person were in the same place at the same time. In fact, while the average student in our data has over 110 Facebook friends, they have only six "picture friends," a number very similar to the number of "close" friends people list when asked in sociology studies. And when we restrict our analysis to "picture friends," we find that some tastes do indeed spread in interesting ways.

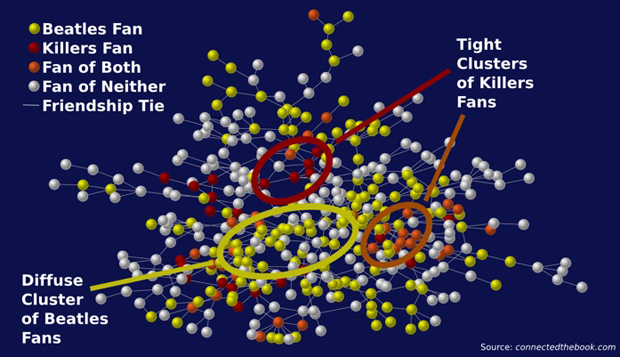

MUSIC. The Beatles, Coldplay, Dave Matthews Band, Green Day, Jack Johnson, Red Hot Chili Peppers, U2, Led Zeppelin, the Killers, and Simon and Garfunkel were the ten most frequently listed groups on the Facebook profiles we studied. Of these, only two showed significant signs of contagion. If a person liked The Beatles, it doubled the likelihood that a friend would like them the following year. Meanwhile, if a person liked the Killers, it increased that likelihood by a whopping 11-fold!

The blue network picture shows the result of these two different intensities of contagion. Much like the real-world obesity epidemic that we have studied, a contagious appreciation of the Beatles appears to be multi-centric, originating in lots of different corners of the network at the same time. In contrast, fans of the Killers were grouped into tight clusters – like the groups of smokers we previously found in our study of the spread of smoking cessation.

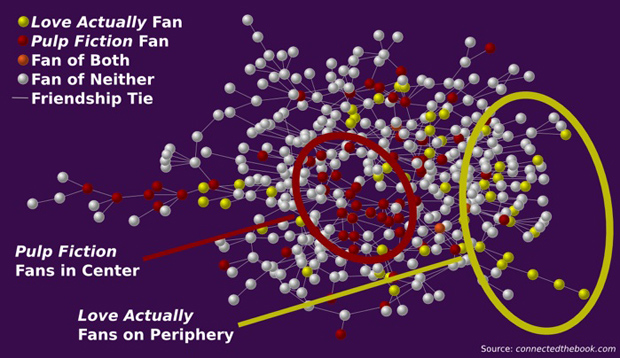

MOVIES. Here the top 10 list included Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, Gladiator, Wedding Crashers, Fight Club, Good Will Hunting, Pulp Fiction, Love Actually, Garden State, and Shawshank Redemption. Of these, only three movies showed evidence of person-to-person spread. People with a friend who liked Love Actually were 4 times more likely to list it as a favorite the following year; those with a friend who liked Pulp Fiction were 5 times more likely to list it; and those with a friend who liked Good Will Hunting were 11 times more likely.

In contrast to the network of musical tastes, the network of movie tastes was quite polarized (much like the well-known polarization of liberal and conservative bloggers on the internet). Hardly anyone had friends who listed both Pulp Fiction and Love Actually. Moreover, these two movies seemed to infect different parts of the network. Pulp Fiction was listed by more "popular" people at the center of the network, while Love Actually was preferred by the wallflowers on the periphery. Businesses often think that they can target influential people at the center of the network to spread news about their product, but that would have been a mistake for a movie like Love Actually. As it turns out, it is not just who we are connected to that matters – it is also how we are connected.

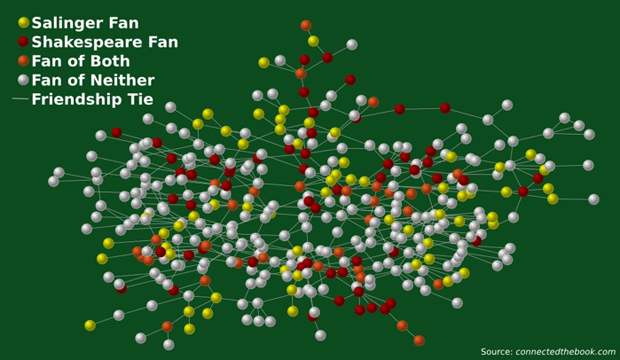

BOOKS. The ten most popular authors were J.K. Rowling, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Jane Austen, J.D. Salinger, George Orwell, Dan Brown, J.R.R. Tolkien, William Shakespeare, Harper Lee, and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Only two of these showed evidence of person-to-person spread. If a friend liked Salinger, it quadrupled the likelihood a person listing him in the following year, while a friend who liked Shakespeare increased the likelihood of a person subsequently listing him by 9-fold.

Although there is evidence that taste in some books can spread online, the green network picture shows that there is no specific pattern to this spread. People who list Shakespeare are just as dispersed and just as likely to be in the center as those who list Salinger, and there is quite a bit of interconnection in these two groups of fans. This many be due, in part, to the fact that both of these authors are frequently assigned in classes (though students are free to list or not list any author they want, according to their own desires). But regardless of the reason, it’s clear that people are more likely to use music and movies than books to define their particular place in the network. We think this is probably because music and movies are explicitly social activities—we often enjoy them together. In contrast, while people may discuss books with each other, reading is a much more solitary event.

While it may be true that "there is no accounting for tastes," the Facebook data can help us see how some of these tastes spread online. When we want to figure out why someone likes this musician or that movie – out of all the musicians and movies in the world – a good place to start is by looking at the tastes of the people to whom he or she is connected. Yet, not just anyone around us can influence us. We might have 1,000 Facebook "friends," but we were not built to affect—or be affected by—all of these people. The spread of influence online works in much the same way that it has worked offline for hundreds of thousands of years. In the past, present, and future, our closest connections are the ones that matter most.